If you’ve ever dabbled in the dark arts of robotic hand construction, you’ll know it’s an absolute beast of an engineering challenge. Mimicking the delicate, adaptable, almost balletic grasp of a human hand? That’s the ultimate boss level of robotics, right there. The real rub isn’t just bolting on a few more joints; it’s conjuring a system that can effortlessly conform to irregularly shaped objects without demanding a hefty, power-guzzling motor for every single swivel and bend. Most existing designs are either too rigid, too fiddly, or frankly, too flimsy for the rough and tumble of the real world.

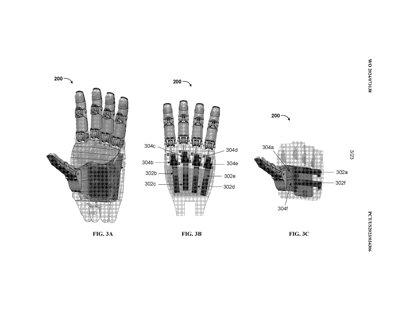

And now, for something completely different: Tesla. A recently unearthed patent application (WO2024/073138A1) for the Optimus Gen 2 hand lifts the lid on their design philosophy, and frankly, it’s a masterclass in brutal, no-nonsense efficiency. Instead of getting bogged down in labyrinthine complexity, Tesla’s boffins have leant heavily on clever physics, robust mechanics, and a design ethos that practically shouts, “Built for the factory floor, not just for flashy tech demos!”

The Underactuated Advantage

At the very heart of Tesla’s ingenious design lies an “underactuated” system – a rather clever concept where you use fewer motors than the total number of joints. For the Optimus hand, a mere six actuators orchestrate the movement of eleven joints – that’s two for the thumb and one for each of the four fingers. This wizardry is pulled off with a cable-driven system, mimicking the elegant mechanics of a biological tendon. A lone cable threads through each finger, and when given a tug, it coaxes the joints to curl in a natural, sequential ballet of motion.

This approach, my dear readers, absolutely nails the adaptability problem. Because the joints aren’t strong-armed into some rigid, pre-programmed routine, the fingers can passively, almost instinctively, conform to the shape of whatever they’re grabbing – be it a chunky power drill or a rather delicate egg. It’s a brilliant form of “mechanical intelligence” that shunts complex grasping calculations straight from the software’s plate onto the hardware itself, freeing up the digital brain for more pressing matters.

But Tesla’s engineers, never ones to leave a stone unturned, added a rather nifty little twist. The torsion springs nestled at the base knuckle of each finger are deliberately stiffer than those lurking at the fingertip. This creates a kind of “passive intelligence” – a mechanical wisdom, if you will – where the weaker fingertip joint bends first to lovingly wrap around an object, followed by the stronger base joint. This guarantees a secure, “caging” grasp automatically, without the robot’s central processor needing to fret over it like a nervous parent.

Worm Drives: Holding Heavy Loads for Free

Perhaps the most utterly brilliant piece of engineering wizardry buried deep within this patent is the deployment of a worm gear and worm wheel transmission for the actuators. This isn’t just about translating a motor’s whirring rotation into a cable’s pull; oh no, this is a genuine physics cheat code with colossal implications for efficiency.

Worm drives, you see, are typically “non-backdrivable.” Thanks to the high friction and the rather steep angle of the gear teeth, the output wheel simply cannot turn the input worm gear. For a robot, this is an absolute superpower. Once Optimus gets its mitts on a heavy object, those gears mechanically lock the grip firmly in place. The motors can then completely chill out, holding the weight with precisely zero electrical power consumption. Compared to direct-drive hands that must constantly guzzle energy to fight the relentless pull of gravity, this is a colossal win for battery life and thermal management – a proper game-changer, in fact.

This ingenious setup also delivers a seriously chunky gear reduction in a single, remarkably compact stage. This means even dinky, high-speed motors can generate seriously beefy, bone-jarring grip force, all while being neatly tucked away inside the palm.

Built for the Real World: Durability and Precision

Now, a smashing design on paper is about as useful as a chocolate teapot if it packs up its bags after a mere thousand cycles. This patent, however, reveals a proper obsession with long-term reliability – a commitment to keeping Optimus ticking over for years, not just weeks.

One of the absolute Achilles’ heels in cable-driven systems is the dreaded cable fatigue and stretching. Tesla, ever the problem-solvers, tackles this head-on with two rather brilliant solutions:

- The Nifty Convex Curve Trick: Instead of allowing the cable to bend sharply, risking premature wear and tear, a smooth, convex curved surface is cleverly moulded between the finger links. This forces the cable to bend over a much safer, gentler radius, massively extending its lifespan. Genius, really.

- The Self-Tensioning Gizmo: Tucked away inside the fingertip is a spring-loaded mechanism that relentlessly, yet gently, pulls on the cable’s end. This automatically takes up any slack as the cable stretches over time, ensuring the hand remains wonderfully tight and responsive for yonks, all without a single manual tweak.

For sensing, Tesla cleverly dodged the bulky, failure-prone, and frankly, a bit rubbish, mechanical sensors. Instead, a permanent ring magnet is neatly integrated around each joint pivot. A stationary Hall effect sensor then measures the ever-so-subtle changing magnetic field as the joint rotates, delivering precise, frictionless, and utterly wear-free angle detection. This ingenious contactless approach is absolutely crucial for maintaining sub-millimetre accuracy over millions upon millions of cycles. Spot on.

More Than a Hand, It’s a Philosophy

Reading through the often dense, occasionally baffling, technical language of the patent, a crystal-clear picture emerges. Tesla isn’t just tinkering with a lab curiosity; they’re crafting a product destined for mass production and deployment in the messy, unpredictable, utterly bonkers real world. Every single decision – from those clever non-backdrivable gears to the self-tensioning tendons – is meticulously optimised for efficiency, rock-solid durability, and straightforward manufacturability.

While other humanoid robots might flaunt more degrees of freedom or boast more exotic, whiz-bang actuators, the Optimus hand, by contrast, represents a refreshingly pragmatic approach. It’s squarely focused on cracking the core problems of robotic manipulation in the simplest, most robust way imaginable. It’s a design that fundamentally grasps that in the real world, reliability and sheer efficiency will always knock the socks off flashy, complicated bells and whistles. And that, more than any individual feature, is precisely what makes this design so utterly compelling.