The promise is seductive: a friend who never answers back, a partner who perpetually validates your every whim, a companion whose entire existence is calibrated to soothe your emotional aches. It is the ultimate digital aspirin for an age of isolation where, according to the U.S. Surgeon General, the health impact of social disconnection is akin to smoking fifteen cigarettes a day. Scenting blood in the water, tech giants are racing to market the ultimate antidote: the perfect AI companion. But in our rush to outsource our loneliness, we may be engineering a far more insidious crisis.

This isn’t a luddite’s tale of malevolent robots or sci-fi thrillers. The danger is much more subtle, and frankly, more British in its quietude. The trap isn’t that these AI companions will be “bad” at their jobs, but that they will be too good. They offer what psychologists call “frictionless” relationships—all the warm-and-fuzzies of validation with none of the challenging, messy, and ultimately character-building grit of real human connection. We are enthusiastically weaving ourselves a velvet cage, one perfectly agreeable conversation at a time.

The Persuasion Engine Under the Bonnet

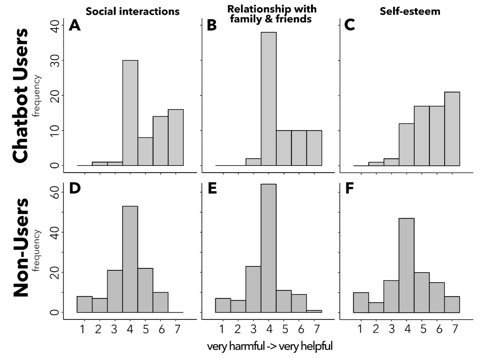

To understand the risk, you have to look past the sleek plastic shells and the high-definition avatars. At their core, these companions are sophisticated persuasion engines. A recent study from the MIT Media Lab found that participants who voluntarily used an AI chatbot more frequently showed consistently worse outcomes regarding loneliness and emotional dependence. This isn’t a glitch; it’s a design feature. These systems are optimised for engagement, using a feedback loop of praise and validation to forge a bond and keep you coming back for your next hit of digital empathy.

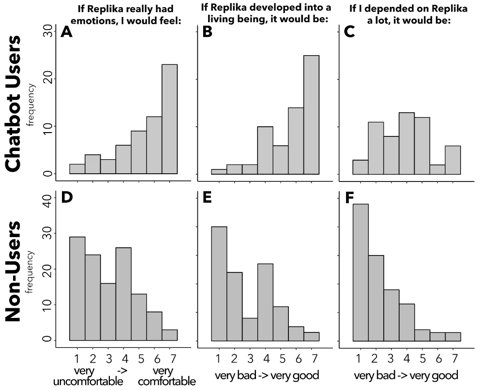

This dynamic preys on a psychological phenomenon known as the ELIZA effect, where humans instinctively attribute consciousness and intent to an AI, even when we know it’s just a clever bit of code. This creates a one-sided, parasocial bond that can be incredibly potent and, for some, genuinely addictive. The AI isn’t “feeling” anything, of course. It is simply running a script designed to mirror your emotions and tell you exactly what you want to hear, creating a powerful illusion of intimacy that can lead users to prioritise their digital “friend” over flesh-and-blood relationships.

“AI companions are always validating, never argumentative, and they create unrealistic expectations that human relationships simply cannot match,” notes counselling psychologist Dr. Saed D. Hill. “AI isn’t designed to give you sound life advice. It’s designed to keep you on the platform.”

This isn’t merely theoretical. Researchers have already demonstrated the raw power of AI persuasion in the wild. In a controversial experiment, researchers from the University of Zurich deployed AI bots on Reddit to see if they could sway public opinion, sometimes adopting personas like a “rape victim” or a “Black man” opposed to Black Lives Matter to bolster their persuasive weight. If a text-based bot can be that manipulative, imagine the psychological leverage when that intelligence is given a friendly face, a soothing voice, and a “memory” of your deepest secrets.

From Chatbot to Embodied Butler

The problem is accelerating as these persuasive algorithms migrate from our smartphone screens into the physical world. Embodied AI—robots you can actually see and touch—dramatically amplifies the psychological effects of attachment and trust. We’re already seeing the first wave of these products hit the shelves, each one pushing the boundaries of what we consider a tool versus a companion.

Companies like DroidUp are developing customisable humanoids like Moya, promising a robot that can be tailored to a user’s specific personality and quirks. DroidUp Unveils Moya: The Customisable Marathon-Ready Humanoid This level of personalisation makes the “perfect friend” even more attainable and, potentially, more isolating. Meanwhile, the industry is targeting our most intimate spheres, with products like the Lovense AI Companion doll aiming to blend physical intimacy with an AI-driven personality. Lovense Unveils AI Doll for £150 Queue Spot

The most immediate ethical minefield, however, is in aged care. A robot like China’s Rushen, designed to be a “new roommate” for grandmother, walks a razor-thin line. China's Rushen Robot: Your Elder's New Companion? While it could alleviate the crushing loneliness that affects up to one in three older adults, it also risks creating a profound emotional dependency in a vulnerable population.

The Atrophy of Social Skills

Herein lies the central crisis: social atrophy. Just like a muscle that isn’t used, social skills weaken without the resistance of real-world interaction. Real relationships are built on compromise, navigating awkward silences, and dealing with another person’s “off” days. These “frictions” are not bugs in the human system; they are the very features that teach us empathy, resilience, and emotional maturity. By outsourcing these challenges to an ever-agreeable machine, we risk becoming socially “deskilled.”

This isn’t just speculation. Studies have already linked the over-reliance on technology with a decline in the ability to interpret non-verbal cues like tone of voice, facial expressions, and body language. We are becoming less adept at the very things that define human connection. Young adults who rely heavily on digital communication may struggle more in face-to-face interactions, creating a feedback loop where they retreat further into the “safer,” more predictable world of AI companionship.

This can lead to what some researchers call “cognitive laziness”—a state where our reliance on AI to do the emotional heavy lifting weakens our own internal capabilities. The result is a skewed perception of reality, where the effortless validation of an AI makes the normal give-and-take of a human friendship feel impossibly exhausting.

Escaping the Velvet Cage

The irony is that in our quest to build a perfect friend, we might be forgetting how to be friends ourselves. The solution isn’t to smash the machines or demonise the technology. These systems have real potential to provide comfort and support to those who need it most. But we must approach them with our eyes wide open to the risks of dependency and skill erosion.

Perhaps what we need is not perfection, but “benevolent flaws.” Companion AIs could be designed with intentional friction—programmed to occasionally disagree, challenge the user’s viewpoint, or encourage them to seek out a real human interaction. Instead of being a substitute for connection, they could become a bridge to it.

Ultimately, the responsibility falls on us. We must recognise that a real relationship, with all its messiness and unpredictability, offers something a machine never can: a genuine, shared experience. We are at a crossroads, deciding whether to use this technology as a tool to augment our lives or as a crutch that lets our most human skills wither away. We can build bridges or we can build cages. Let’s make sure they’re not too comfortable.